The new model mental health clinic at Gongoni in Magarini. Photo Credit, ALPHONCE GARI.

“The pain of a child is known to the parent.” This saying resonates deeply with Regina Mwendo, a 76-year-old mother of nine from Vibao Viwili Village in Tana River County, Kenya.

For over ten years, Regina has embarked on a grueling journey from Tana River County to Malindi Sub-County Hospital in Kilifi County, seeking mental health treatment for her two children. The journey, starting at six in the morning and spanning four and a half hours, has become a routine part of her life after every two months.

Tana River County is one of the six counties in the coast region. It borders Kilifi County to the south.

As she arrives at the hospital by 10:30 AM, she joins over 15 other patients waiting to see a psychiatrist. Clad in a purple velvet dress, with a leso draped over her shoulder and a pink checked headscarf, Regina carries a brown handbag filled with record books documenting her children’s medical history. These records, some dating back to 2014, are crucial for doctors to track the progress and treatment of her children’s conditions.

“I have traveled all the way from Tana River to come and get medicine for my two children who have mental disorders. I have been doing this for more than ten years now,” she says, smiling.

Regina’s firstborn son, Shadrack Nzomo, 56, was first diagnosed with mental disorder immediately after completing high school. “The doctors said it was because of studying too much since he was always top of his class,” Regina recalls.

With no local facilities offering the necessary services, Regina and her husband took Shadrack to Mathare Mental Hospital in Nairobi approximately 456 kilometers from Tana River County. After receiving treatment, he was able to return to school while continuing with his medication.

Her second child, Patricia Nzomo, 53, was also diagnosed with a mental disorder while in form three.

“My firstborn was diagnosed immediately after finishing high school and was set to join university. While taking care of him, his sister also started showing the same behaviors,” Regina explains.

“It was a very difficult and challenging time. They sometimes became violent, undressed, and ran to the nearby forests. We sometimes had to involve the police to help catch them,” she adds.

Sidi Kalume, a journalist from Kibojoni Village in Kilifi County, is a survivor of mental illness. Sidi never realized she had mental issues and carried out her journalism duties without a hitch. Her family and close friends noticed something was amiss and decided to take her for a mental checkup.

“As I was recovering, my family told me how it started. I exhibited signs such as erratic behavior, excessive talking, and anger. These early signs prompted my family to take me to the hospital,” Sidi recounts.

Sidi said despite the challenges, her mother remained supportive, helping her navigate the difficult journey back to health.

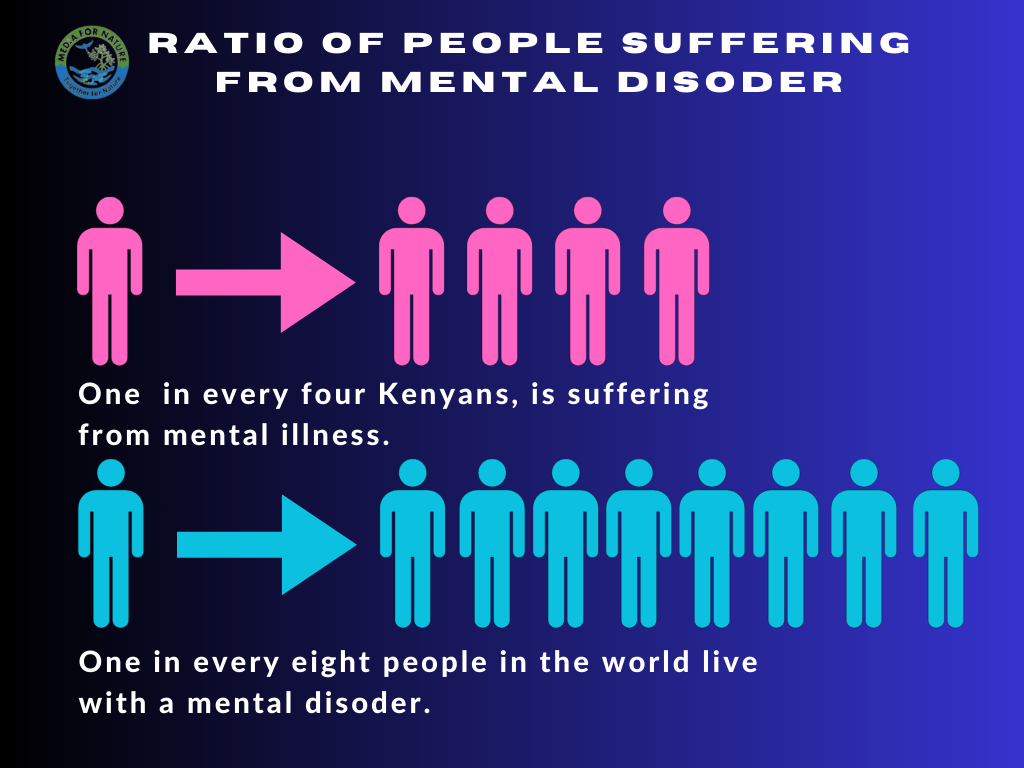

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 1 in every 8 people in the world live with a mental disorder. While Health experts in Kenya projects that 1 out 4 Kenyans is suffering from a mental illness ranging from mild to severe disorders.

Mental disorder is characterized by a clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotional regulation, or behavior. It is usually associated with distress or impairment in important areas of functioning.

Mental disoder graph. Credit, Ruth Keah.

Stigma

After receiving treatment at Mathare Hospital, Shadrack managed his condition successfully for eight years, even getting married and fathering five children during this period. However, his mental disorder occurred again, leading his wife to leave him and return to her family.

“The situation was on and off, and the wife started fearing him. Eventually, she confessed to me that she couldn’t continue living with him in that condition and she left,” Regina recounts.

Patricia – Regina’s daughter, faced a similar fate. Unaware of her previous mental health struggles, her husband discovered her condition after the birth of their second child. Regina took Patricia to the hospital for treatment while also caring for her grandchildren. When Patricia’s condition stabilized, she stayed with her mother, as her husband showed no interest in supporting her.

“Instead of taking my daughter to the hospital, her husband abandoned her. The neighbors took her to the hospital in Taveta, where she was married, I was later informed and went to look after her, her husband never came for her even after managing the situation,” Regina reveals.

Regina Mwendo at the Malindi subcounty Hospital mental health clinic centre. Photo Credit, Allan Kai.

Sidi, on the other hand, said she faced a toxic environment due to her mental illness.

“Some people in my village were even happy for my downfall, some distanced themselves from me, fearing I might become violent. I was confused by their behavior,” she says.

To combat the stigma surrounding mental illness, Beatrice Njeru, a registered psychiatric and mental health practitioner at Malindi Sub-County Hospital in Kilifi County, explained that they utilize mental health champions to raise awareness and demonstrate that the condition is treatable.

Through their efforts, they hope to eradicate discrimination against patients and promote understanding within the community.

Dr. Janbib Mohammed, a psychiatrist working for Mombasa County and the Mombasa Women Empowerment Network as part of a private-public partnership, emphasizes the critical need for accessible mental health services. The network operates a fully accredited Rehabilitation and Treatment Center in the Miritini area of Mombasa County, aimed at supporting individuals who lack the financial means to access private or government mental health facilities. This center is a beacon of hope for underserved populations, providing essential treatment and resources.

Dr. Mohammed explained that mental illness is often understood through a psychosocial model, which involves a combination of factors. “How someone processes stressful events—such as living in war zones, losing a job, experiencing divorce, substance use, and various social and environmental factors—can contribute to mental illness. When we observe a change in someone’s routine life, it’s then that we recognize something is not right mentally,” she said.

She also noted the impact of societal changes on mental health. “The shift in societal culture, like social media, has created more isolation than before. There are fewer person-to-person interactions than there used to be,” she added.

Challenges

Sidi said her mental illness not only impacted her own life but also took a toll on her family members. Her life took a drastic turn due to her illness. As someone who was employed and self-sufficient, she became unable to work, eventually losing her job. Her family had to bear the burden of her medical expenses.

“My mental illness also affected my family members because when I wasn’t happy, they weren’t happy either. They were always by my side—my brothers, sisters, and my parents,” she shares. “My parents had to stay at home to look after me, to ensure I didn’t run away. It was truly heart-wrenching.”

Regina said despite her own health challenges of diabetes and high blood pressure, she continues to travel from Tana River to Malindi to save on the high cost of medication for her children’s mental health.

“Travelling from Tana River to Malindi costs me approximately Ksh 2,000, and then there’s the cost of the medication itself,” she explains. “To reduce the expenses for two people, I make the journey myself, saving money in the process.”

“For instance, today I’ve been told to buy drugs which will cost me Ksh 3,000, and they will last for two months only,” Regina adds.

Overcoming the disease

The Kenya Mental Health Policy 2015-2030 estimates that the burden of mental illness is 25% among outpatients and 40% among inpatients in different health facilities, with an estimated prevalence of psychosis stated as 1% of the general population.

The report further provides for a framework on interventions for securing mental health systems reforms in Kenya. This is in line with the Constitution of Kenya 2010, Vision 2030, the Kenya Health Policy (2014- 2030) and the global commitments.

Beatrice Njeru, a registered psychiatric/mental health practitioner at Malindi Sub-County Hospital in Kilifi County, along with two other doctors, work tirelessly in the mental health clinic, where the demand for services is evident through frequent interruptions during my interview with her.

Beatrice said the facility encounters various mental illnesses cases including anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression, with substance abuse being a major contributor to cases.

She said substance abuse, including Mugukaa, Miraa, heroin, bhang, tobacco, and injection drugs, often serves as a primary cause of depression. She said the prevalence of mental health issues is increasing in the county, with approximately 1 in 4 individuals affected.

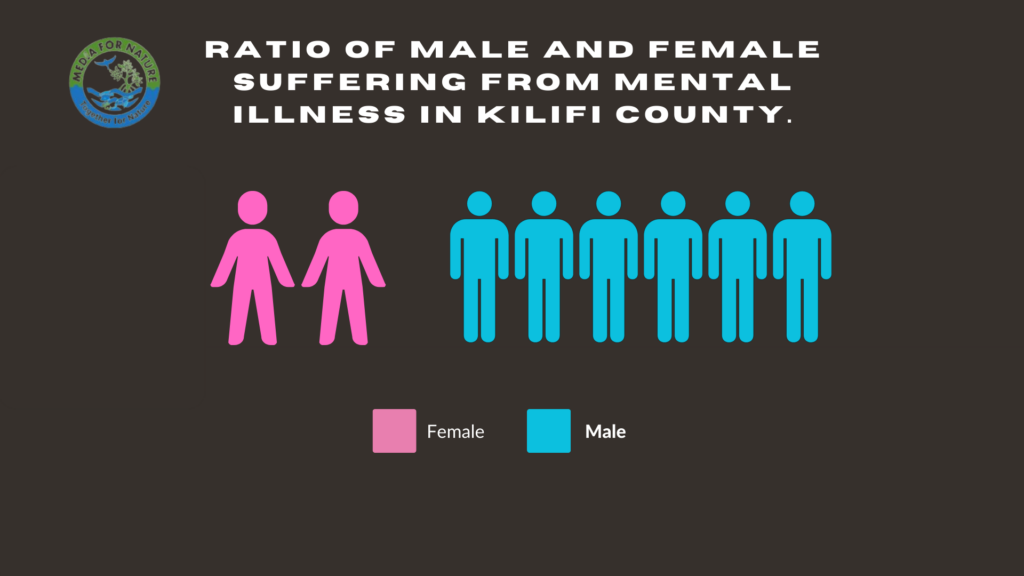

At the center, they typically receive 5-10 new patients, with revisits totaling up to 20 patients in a day. Males are disproportionately affected, with a ratio of 2:6 compared to females.

Kilifi Graph. Photo Credit, Ruth Keah.

She said with the assistance of community health promoters, individuals with mental illness are identified and enrolled in the appropriate centers.

Kilifi County boasts three primary mental health clinics located at Malindi Sub-County Hospital, Mariakani Sub-County Hospital, and Kilifi County Referral Hospital. Additionally, three newly established centers in rural areas at Ganze, Kaloleni, and Gongoni being the latest opened in April 2023 to serve the community.

The rural clinics operate once per week and cater to up to 50 patients during the visit.

According to Beatrice, the rural clinics have significantly contributed to reducing stigma and encouraging more individuals with mental illness to seek medical services.

“Through the rural clinics, people have begun to understand that mental illness is not witchcraft but a treatable medical condition”, she said.

“We work closely with the community health promoters to pinpoint cases of mental illness in the community and ensure they are enrolled in our centers. Through this collaboration, we can effectively reduce the number of chronic cases being managed at home,” she explained.

Beatrice Njeru, a registered psychiatric/mental health practitioner at Malindi Sub-County Hospital in Kilifi County. Photo Credit, Allan Kai.

Regina, relieved by the establishment of mental health clinics in Kilifi County, she no longer needs to travel to Nairobi or Mombasa for medication. She said since she started receiving treatment at the Malindi Sub-County Hospital, her children have made significant progress, and are now able to work and assist with daily tasks.

“Shadrack is now a cobbler and can engage in farm activities at our farm, while the second born is a cook at a nearby school in Tana River,” she said.

“For now, I can say the life my children are living is not bad. At first, I used to get hurt since I had to do everything for them, including washing, clothing, and cooking for them. But now, with the medication, each one of them can take care of themselves,” she concluded.

Similarly, Sidi, said she can now access monthly checkups with ease, thanks to the nearby rural mental clinic at Kaloleni.

However, despite these advancements, Ms. Njeru said challenges persist. Staff shortages, drug shortages, and the high cost of medication remain pressing issues.

Dr. Mohammed said the consequences of delayed treatment are severe.

“Late treatment can lead to many consequences, including losing jobs, divorce, losing important interpersonal relationships, missed opportunities, becoming violent, damaging property, and sometimes ending someone’s life”, she said.

Dr. Mohammed said despite the urgency, mental illness remains a neglected field. She emphasized the importance of rural mental health services to address the rising number of cases.

“If you are treating someone’s mental health, number one, you are contributing to their overall good health. Mental health issues exist in every community, society, and institution, meaning anyone can suffer from mental illness. So, it is important to have treatment centers and places where people can be attended to everywhere across,” she emphasizes.

A survey released by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) shows that in 2018, there were 104,615 cases of mental illnesses reported in hospitals across the country. With Mombasa leading among the coastal counties with 4,620 cases, followed by Kilifi 2,353, Taita Taveta 2,242, Kwale 1,011, Lamu 734, and Tana River 519.

According to Beatrice, Kilifi County has registered 7,000 mental health patients this year alone.

Regina passionately called upon the government to prioritize affordable medication for individuals struggling with mental illness.

“At first, we received medication for free from Nairobi, Mombasa, and even here in Malindi. But for the past five years, things have changed. We are now paying for medication which is very expensive,” she laments.

On her side, Sidi emphasizes the critical impact of proximity in accessing medical care for mental illness.

“When a medical clinic is nearby, it greatly assists individuals with mental illness in obtaining medication easily hence facilitating their recovery,” she stresses.

She urges against misconceptions, particularly in rural areas, urging communities not to view mental illness as untreatable or witchcraft, but rather to seek medical help to reduce stigma and provide necessary support.

“People with mental illness are treatable. Don’t leave them wandering on the streets. Early hospitalization and treatment enable them to regain their senses, resume work, and care for themselves,” she emphasizes.

Beatrice said there is need for a psychiatric unit within Kilifi County to address the surging demand for mental health services, advocating against overcrowded referral centers.

“When we encounter violent patients requiring in-house monitoring, we refer them to Portreitz Hospital in Mombasa, sometimes it’s a challenge because the Centre has an overwhelming patient load,” she concluded.

With the increase of health illness cases in the country, a report by the Taskforce on Mental Health in Kenya conducted in 2020 recommended the increase of numbers of mental health units in the counties. And each unit should be run by a minimum staffing of a psychiatrist, a psychiatric nurse, and a social worker.

This minimum standard of staffing the task force said will ensure adequate supervision is provided to trainee health care workers as well as the population served.

Dr. Mohammed on her side emphasized the importance of mental self-care.

“Just as people exercise their bodies by going to the gym, we should practice the same self-care for our brain and mental health. Simple things like self-love, self-care, taking a walk, good nutrition, taking time to relax, and having social interactions with other people to avoid loneliness are essential. These practices ensure good mental health,” she concluded.

This story was made possible by the support of the UZIMA–DS project, funded by the national institute of Health (NIH).